Mastering useEffect - Summary and Understanding Notes from Dan Abramov's "A Complete Guide to useEffect"

useEffect is arguably one of the most important yet challenging Hooks to understand in React. Previously, I briefly introduced useEffect in this section article. Now, let's dive deeper into understanding useEffect through former React team member Dan Abramov's comprehensive article: A Complete Guide to useEffect — overreacted.

Table of Contents

- Each Render in useEffect is Independent with Its Own Everything

- If You Need to Read the "Latest" Value in useEffect, Use Another Hook: useRef

- About the Execution Timing of useEffect Cleanup Mechanism

- Synchronization, Not Lifecycle

- About the Purpose and Working Principles of useEffect Dependencies

- Don't Lie to React About useEffect Dependencies

- useEffect Usage Strategies

- Conclusion

- Reference

Each Render in useEffect is Independent with Its Own Everything

First, in the sections "Each Render Has Its Own Props and State," "Each Render Has Its Own Event Handlers," "Each Render Has Its Own Effects," and "Each Render Has Its Own… Everything," we learn that each render in function components creates a complete "snapshot" containing:

-

Props and State: These props and state are immutable constants, not dynamically bound. It's crucial to understand they're just plain numbers that don't "listen" for state changes and automatically update.

-

Event handlers: Event handlers "capture" the state value at the moment of the click. Each event handler "belongs" to a specific render and remembers that render's state value. This relates to JavaScript's closure mechanism - each function remembers the environment variables when it was created.

-

Effects: It's important to note that effects themselves aren't "listening" for state changes. Instead, each time is a completely new function. In other words, with each render, React gets a brand new effect function, and each effect function "sees" the props and state belonging to its specific render.

-

All other variables and functions

This "render isolation" is completely different from class components where this.state always points to the latest value. Understanding this difference is key to mastering useEffect and the entire Hooks mental model. Each render is independent with its own everything, making React's behavior predictable and easy to understand.

If You Need to Read the "Latest" Value in useEffect, Use Another Hook: useRef

After understanding the concept of render isolation in useEffect, we might face a dilemma: what if we genuinely need to read the "latest" value instead of the "captured" value in certain situations?

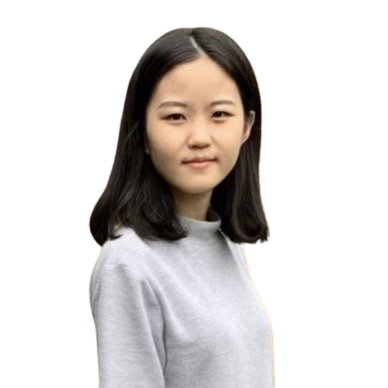

Dan compares this approach to "swimming against the tide," and the solution is to use another Hook: useRef. Here's a specific example:

When you need the "latest" value, using useRef is the correct escape hatch, but use it cautiously as it breaks the purity and predictability of functional components.

Other considerations:

1. Reasonableness of Mutation

While mutation looks strange in React, this is exactly how React reassigns this.state in class components.

2. No Guarantees

Reading latestCount.current cannot guarantee you'll get the same value in any specific callback, because it's inherently mutable.

3. Non-default Behavior

This approach isn't the default behavior - you must explicitly choose to use it, which is an intentional design decision.

About the Execution Timing of useEffect Cleanup Mechanism

Next, in the "So What About Cleanup?" section, we can correctly understand the execution timing of useEffect's cleanup mechanism to avoid common misconceptions about effect execution timing.

Wrong Mental Model

Many developers are used to thinking about useEffect in terms of class component lifecycle, believing:

-

React first cleans up the old effect (corresponding to

{id: 10}) -

React re-renders the UI (corresponding to

{id: 20}) -

React runs the new effect (corresponding to

{id: 20})

But this understanding is completely wrong.

Actual Execution Order

The real execution order is:

-

React renders UI (corresponding to

{id: 20}) -

Browser paints, user sees the new UI

-

React cleans up the previous effect (still

{id: 10}) -

React runs the new effect (corresponding to

{id: 20})

As for why cleanup can see the old props, this was already explained in the previous section about render isolation - the key concept is closure.

This design has two important advantages:

-

Performance optimization: Effects run after browser painting, not blocking UI updates, making applications faster.

-

Logical correctness: Ensures cleanup always correctly cleans up the corresponding effect, avoiding memory leaks or incorrect unsubscriptions.

This allows React to reliably handle effects while providing better performance by default.

Synchronization, Not Lifecycle

If we had to summarize the most important concept from the previous sections in one sentence, it would be "synchronization, not lifecycle."

Dan emphasizes this crucial mental shift in the "Synchronization, Not Lifecycle" section: we should view useEffect as a synchronization tool rather than lifecycle methods.

This mental shift has profound implications for writing useEffect:

-

Break away from traditional lifecycle thinking, don't think "do X on mount, do Y on update"

Although I learned programming and encountered React relatively late, so I personally didn't go through the class component phase, according to Dan's article, the traditional mindset makes us think about:

-

mount: what to do when the component first appears

-

update: what to do when the component updates

-

unmount: what to do when the component disappears

Dan emphasizes this is the wrong way of thinking. If you try to write an effect that behaves differently based on "whether it's the first render," you're fighting against React's design philosophy.

-

-

Instead, think "ensure external resource Z always reflects current props and state"

One of React's most elegant features is that it unifies the description of initial render and updates. Whether a component is rendering for the first time or updating subsequently, we describe what the UI should look like in the same way. In other words, when using React function components, we should have a "goal-oriented" mindset rather than a "process-oriented" one.

"Goal-oriented" vs. "Process-oriented" Differences

-

jQuery approach: Focus on "process" - we need to manually call

$.addClassand$.removeClass -

React approach: Focus on "goal" - we directly specify what the CSS class should be

This is the difference between "journey vs destination." React lets us focus on the final state without worrying about how to transition from state A to state B.

-

-

Let React decide when and how to execute synchronization logic

This mindset allows us to write more predictable, easier to understand and maintain code, perfectly aligning with React's declarative nature.

Balancing Performance Considerations

However, Dan also acknowledges that executing all effects on every render might not be the most efficient and could even cause infinite loops. This is why React provides mechanisms like dependency arrays for optimization (covered in later sections).

But the key point is: optimization is a later consideration; correctness of synchronization logic is the primary goal.

About the Purpose and Working Principles of useEffect Dependencies

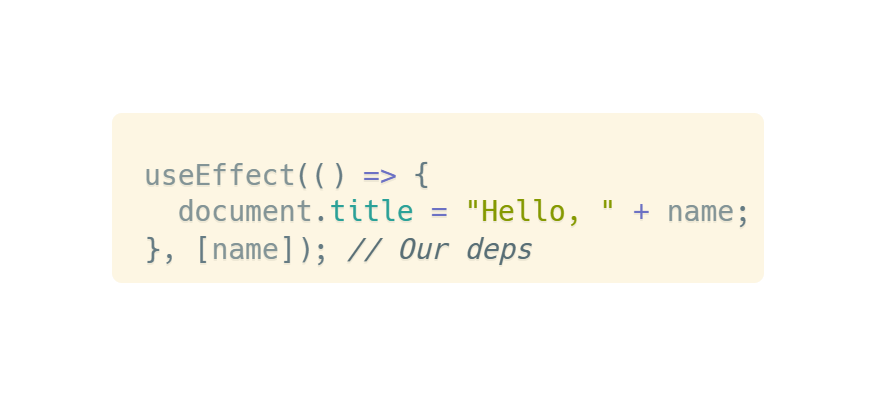

In the "Teaching React to Diff Your Effects" section, we learn how React handles useEffect optimization through dependency arrays.

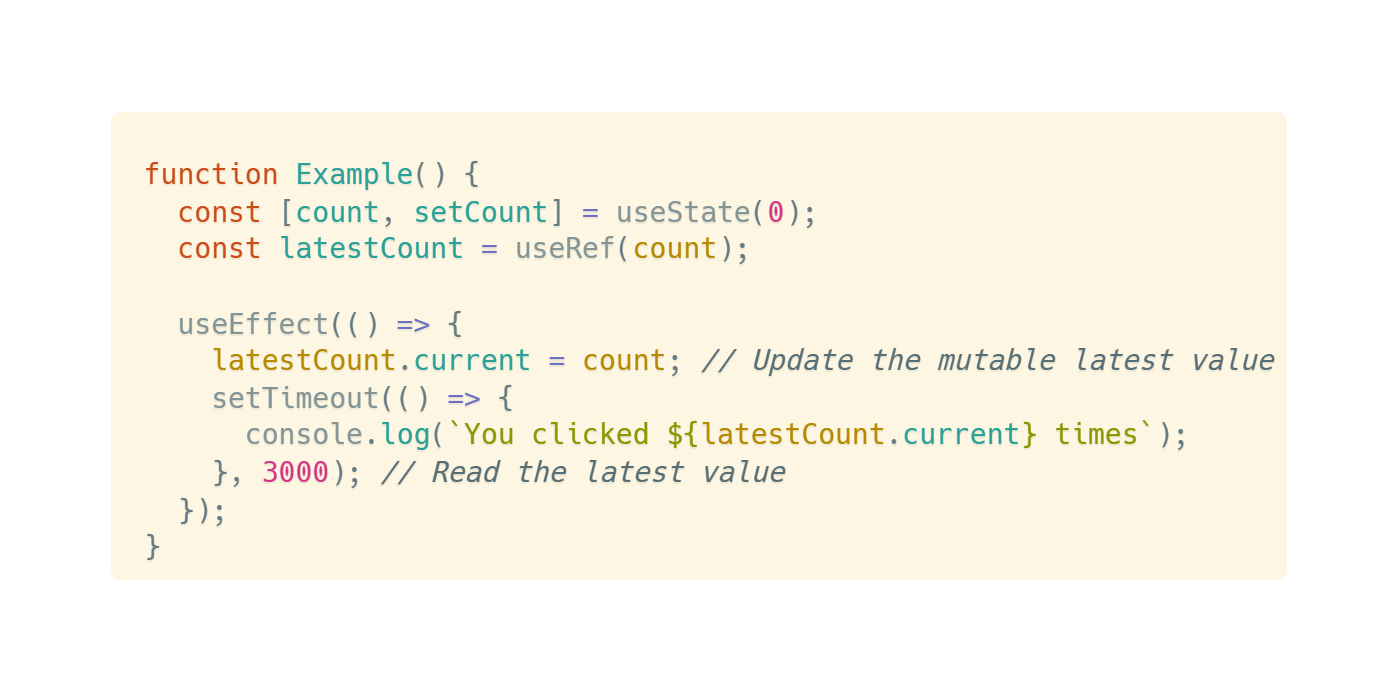

Dan first establishes an analogy: we all know React performs diffing when handling DOM updates, only updating parts that actually changed. For example, when an <h1> content changes from "Hello, Dan" to "Hello, Yuzhi," React compares the before and after props:

React discovers only children changed, so it only executes domNode.innerText = 'Hello, Yuzhi' without touching className.

We then wonder: when executing useEffect, can we avoid unnecessarily re-running effects, similar to how DOM updates are handled?

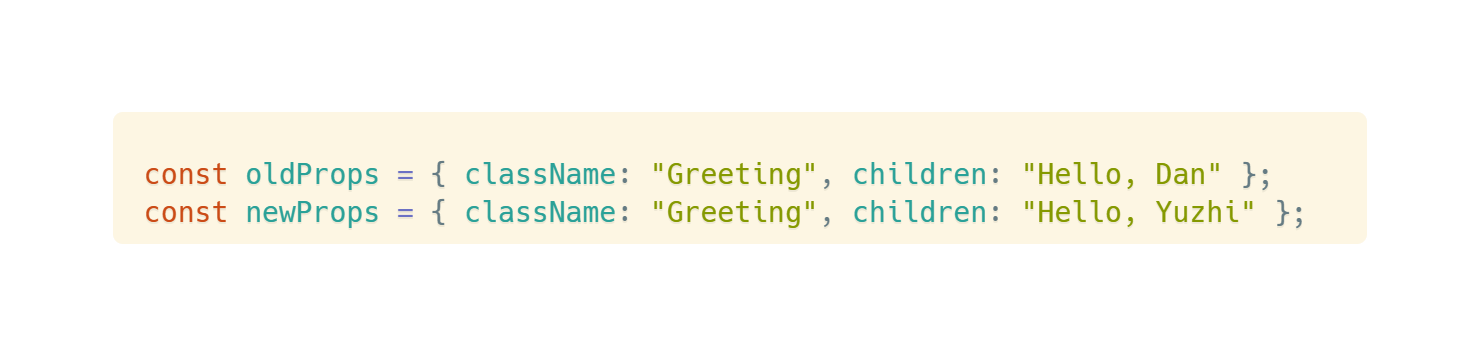

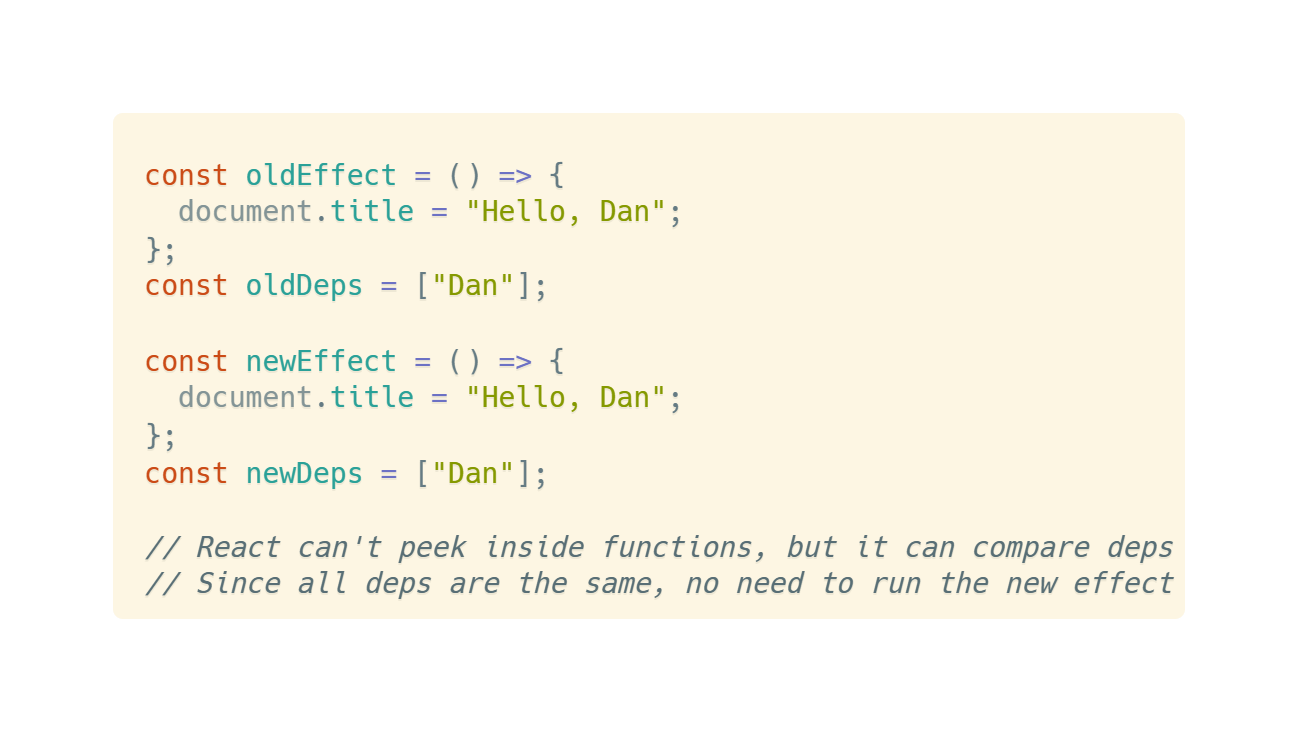

The Challenge: React Can't Directly Compare Functions

Dan explains why React can't directly compare effects like it does DOM props:

For the above code example, React can't tell these two functions are doing the same thing. Even though the code looks identical, functions might close over different variables or props internally. This is why we need dependency arrays.

Solution: Dependency Array

Here's an example of using dependency arrays:

This is like telling React: "Hey, I know you can't see inside this function, but I promise it only uses name and nothing else from the render scope."

When React receives the dependency array, it compares dependencies between renders:

Key rule: If any value in the dependency array differs between renders, React knows it can't skip executing this effect and must re-synchronize.

From this explanation, we understand that React trusts developers to use dependency arrays correctly. React believes the dependency array provided by developers is accurate and complete. It's entirely the developer's responsibility to explicitly tell React which values this effect depends on through the dependency array. This explains why React's linter strictly checks dependency arrays, and why missing dependencies easily leads to bugs - because this is React's only basis for deciding whether to re-run an effect.

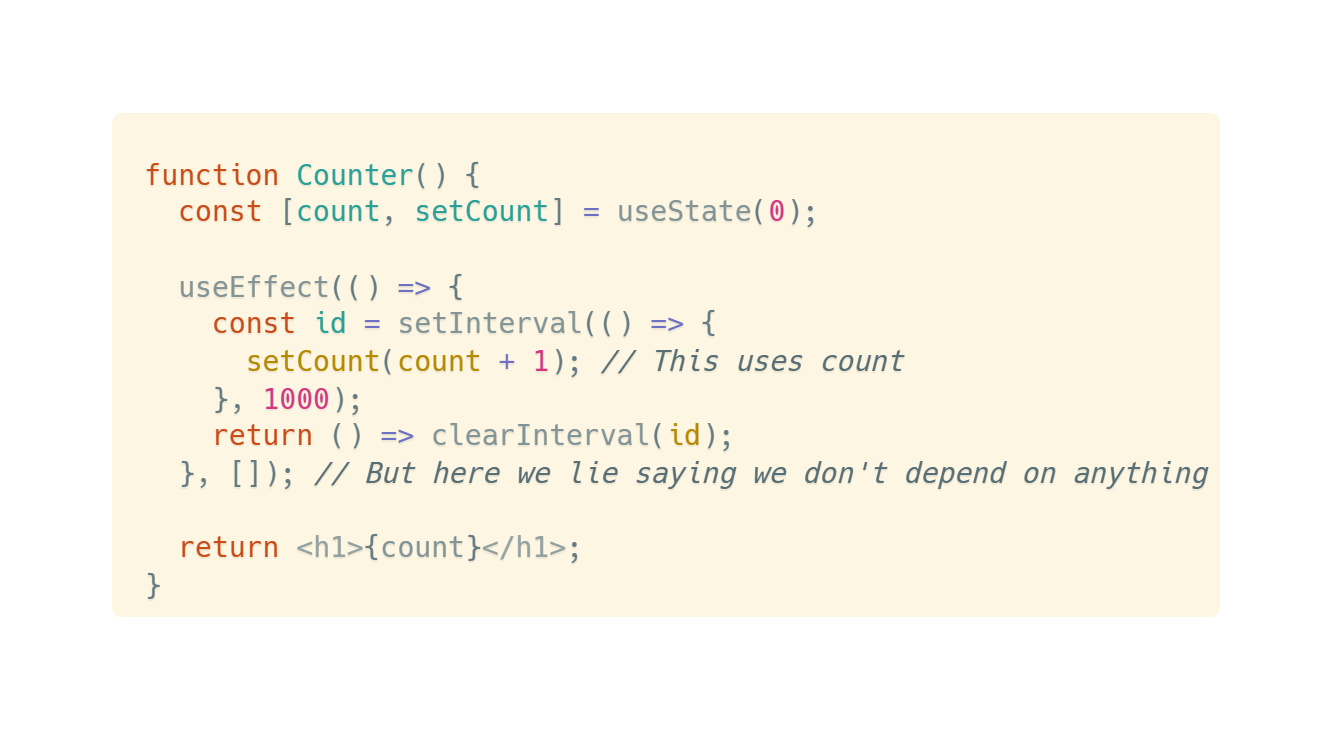

Don't Lie to React About useEffect Dependencies

In the "Don't Lie to React About Dependencies" and "What Happens When Dependencies Lie" sections, we learn that dependencies aren't for controlling "when to re-trigger effects" but for telling React "which values from the render scope the effect uses."

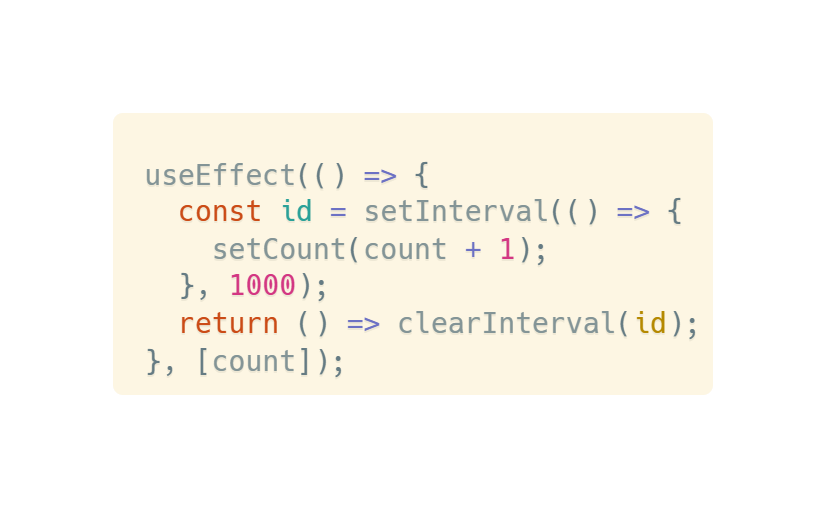

Lying about dependencies easily leads to runtime errors. Here's a classic counter example to illustrate the problem:

Why Does This Go Wrong?

-

Closure trap: On first render,

countis 0 -

Effect won't re-run: Because dependencies are an empty array

[], React thinks this effect never needs updating -

Stale value: The callback in

setIntervalforever remembers thecountvalue from the first render (0) -

Result: Every second executes

setCount(0 + 1), count forever stays at 1

Correct Flow:

-

React compares dependencies between renders

-

If any value changes, re-run the effect

-

If lying (omitting actually used values), leads to stale closure problems

useEffect Usage Strategies

After understanding the important principle of "don't lie to React about useEffect dependencies," let's discuss the most important usage strategies in practice.

In the "Two Ways to Be Honest About Dependencies" section, Dan presents two fundamental strategies for handling useEffect dependencies.

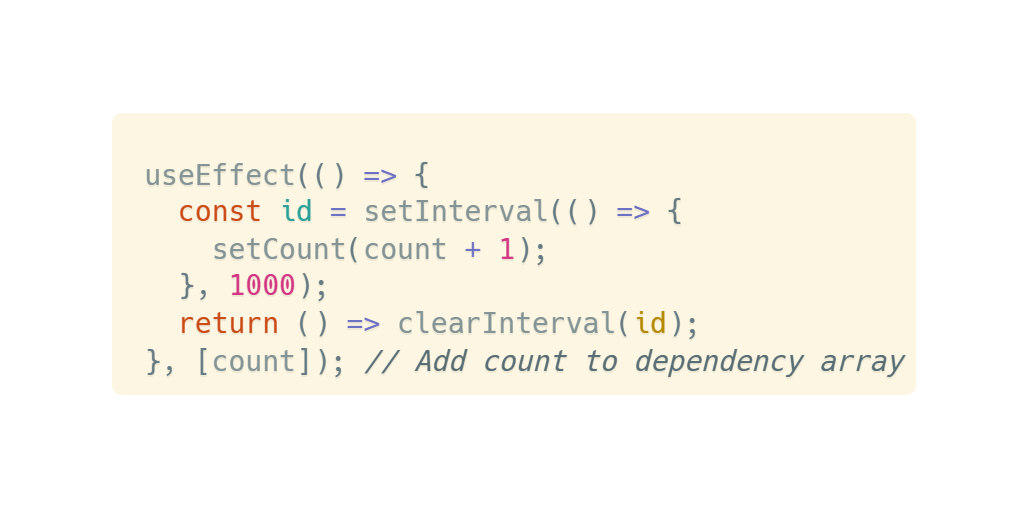

Strategy 1: Ensure Dependency Array Includes All Used Values

The first strategy is to honestly include all component values used inside the effect in the dependency array. This should be the first approach when dealing with dependency issues. Continuing with the counter example:

This strategy ensures dependency array correctness, avoids stale closure problems, and ensures each effect gets the latest values. However, its downside is that effects re-run every time dependency values change, potentially causing performance issues and unnecessary side effects. In the above example, this strategy causes the interval to be constantly cleared and recreated.

Strategy 2: Legitimately Reduce Effect's Dependency on Frequently Changing Values

To solve Strategy 1's drawbacks, we can modify the effect's code so it doesn't need to depend on values that change more frequently than we'd like. Note this isn't about hiding dependencies but redesigning the effect to have fewer dependencies.

The specific implementations of "reducing effect's dependency on frequently changing values" include multiple methods. Let's explain them progressively.

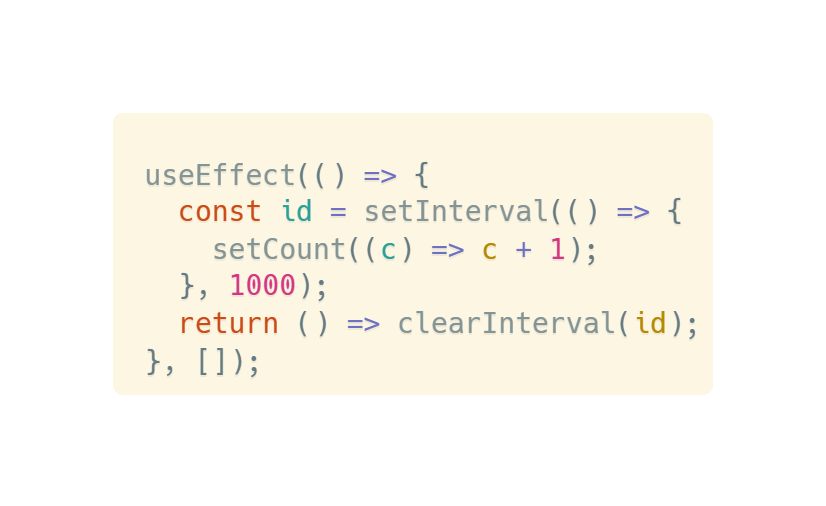

[Method 1: Using Functional Updates]

In the "Making Effects Self-Sufficient" section, Dan explains how to use functional updater methods in useEffect to legitimately remove unnecessary dependencies and solve performance issues.

First, let's review the original problem mentioned in Strategy 1:

In this example, the effect depends on the count variable, causing a problem:

-

Whenever

countchanges, the entire effect re-runs -

The old interval gets cleared, a new interval gets created

-

This is a performance waste and not the behavior we actually want

To rethink dependency necessity, we can ask ourselves an important question: What are we using count for?

The answer is "we're only using it in setCount." This reveals a deeper truth:

-

React already knows the current

countvalue -

We actually only need to tell React "how to change state," not "what value to change to"

Solution: Use functional updates, specific example:

The brilliance of this solution lies in:

1. Eliminating False Dependencies

-

countseems like a necessary dependency but is actually a "false dependency" -

What we really need isn't the

countvalue but the "increment" operation

2. New Mental Model for State Updates

-

Shift from "telling React what the new value is" to "telling React how to calculate the new value"

-

setCount(c => c + 1)can be understood as "sending instructions" to React, indicating how state should change

3. Self-Sufficient Effects

-

Effect no longer needs to read

countvalue from render scope -

Even if effect only runs once, the interval callback still works correctly

-

Each time the interval triggers, it sends the correct update instruction

This mental model applies to broader scenarios:

-

When you find an effect depends on some state value but only to update it

-

When you want to batch multiple updates

-

When you want to avoid unnecessary effect re-runs

This concept emphasizes the importance of declarative programming: we describe "what to do" rather than "how to do it," letting React handle the implementation details.

Next, Dan explains functional updates more deeply in the "Functional Updates and Google Docs" section.

Dan uses Google Docs as an example to explain an important principle: when you edit a document in Google Docs, the system doesn't send the entire page content to the server because that would be too inefficient. Instead, it only sends a representation of "the action the user attempted to perform."

This philosophy applies equally to effects: we should send minimal necessary information from inside effects to the component. To achieve this, we should have awareness of "encoding intent rather than results," similar to how Google Docs solves collaborative editing.

Returning to the previous example, we can compare these two approaches:

-

setCount(c => c + 1)(functional update) -

setCount(count + 1)(direct update)

Functional updates convey less information, but this is actually an advantage because they're not "polluted" by the current count value - they only express the "increment" action itself. This aligns with React's core principle: find the minimal but complete state representation.

However, Dan also admits setCount(c => c + 1) isn't perfect:

-

Syntax looks a bit strange

-

Limited functionality: If two state variables depend on each other or you need to calculate the next state based on props, functional updates can't handle these situations.

[Method 2: Using useReducer]

Therefore, in the next section "Decoupling Updates from Actions," Dan presents a solution for when functional updates can't handle the situation: using useReducer - the "more powerful sister pattern" of setCount(c => c + 1).

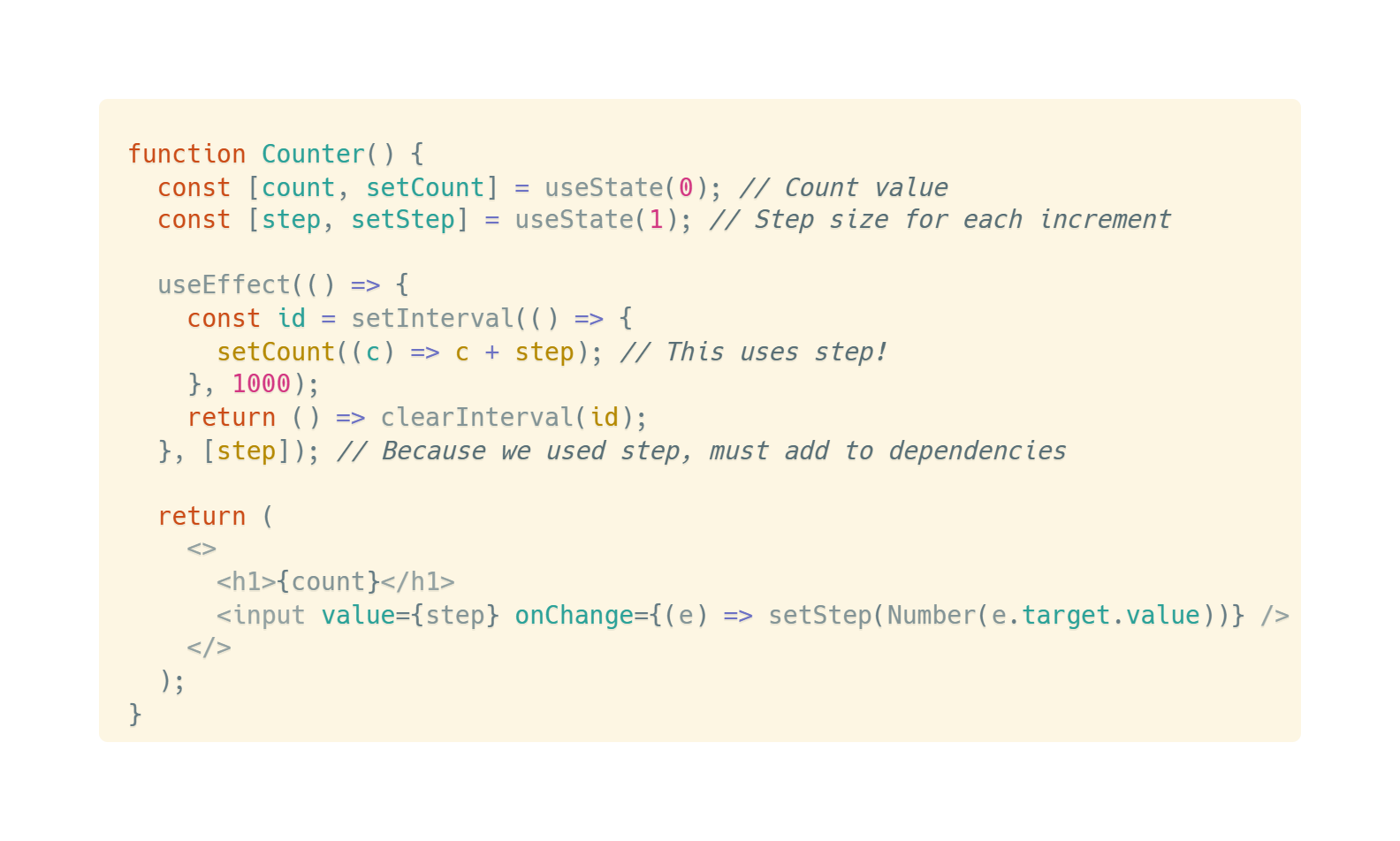

First, consider this example:

Problems with this version:

-

setCount(c => c + step): This line reads thestepvalue -

[step]dependency: Because the effect usesstep, must include it in dependencies array -

Re-execution problem: Whenever user changes the

stepinput value, the entireuseEffectre-runs -

Timer reset: This means

setIntervalgets cleared and recreated, resetting the timer

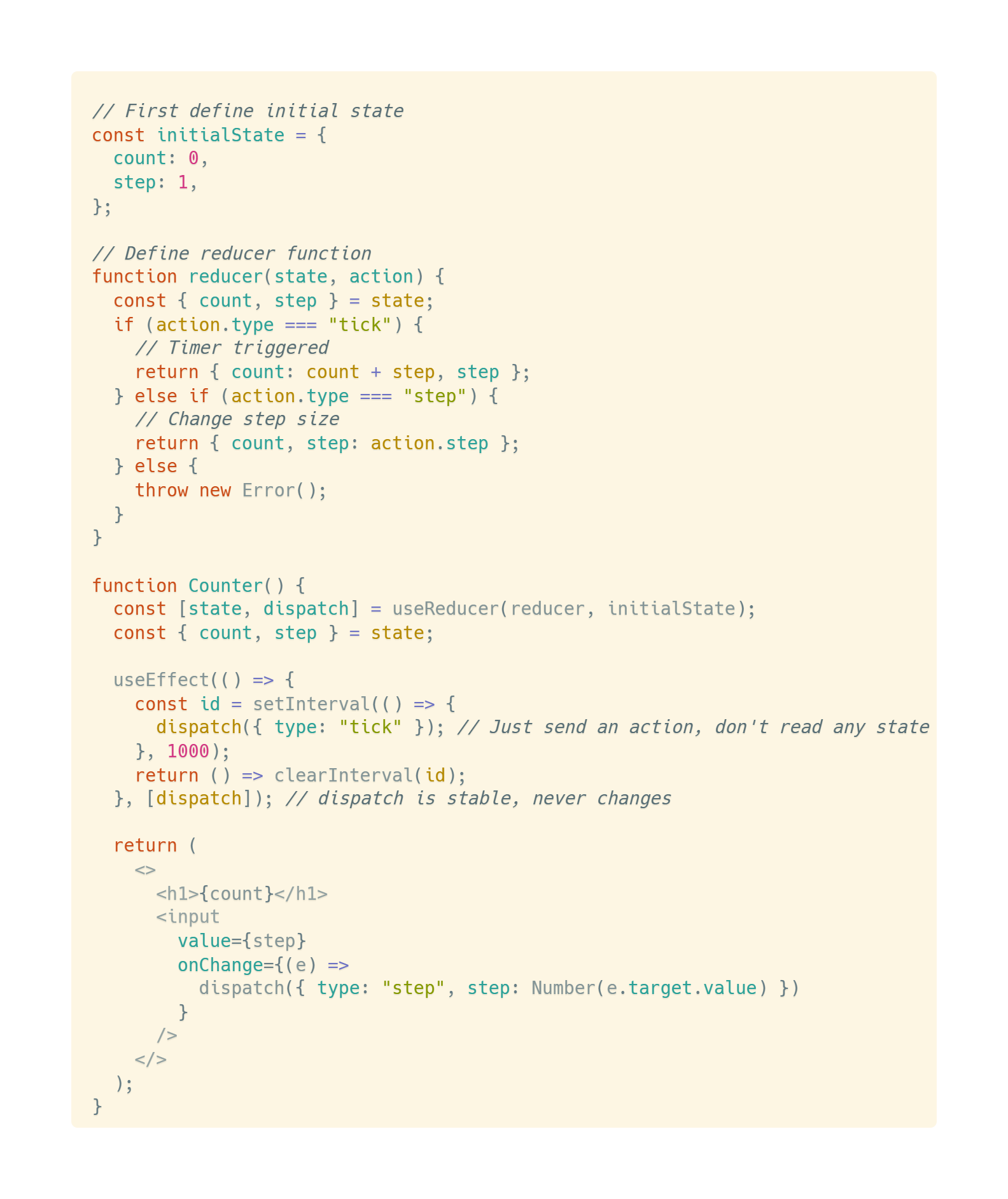

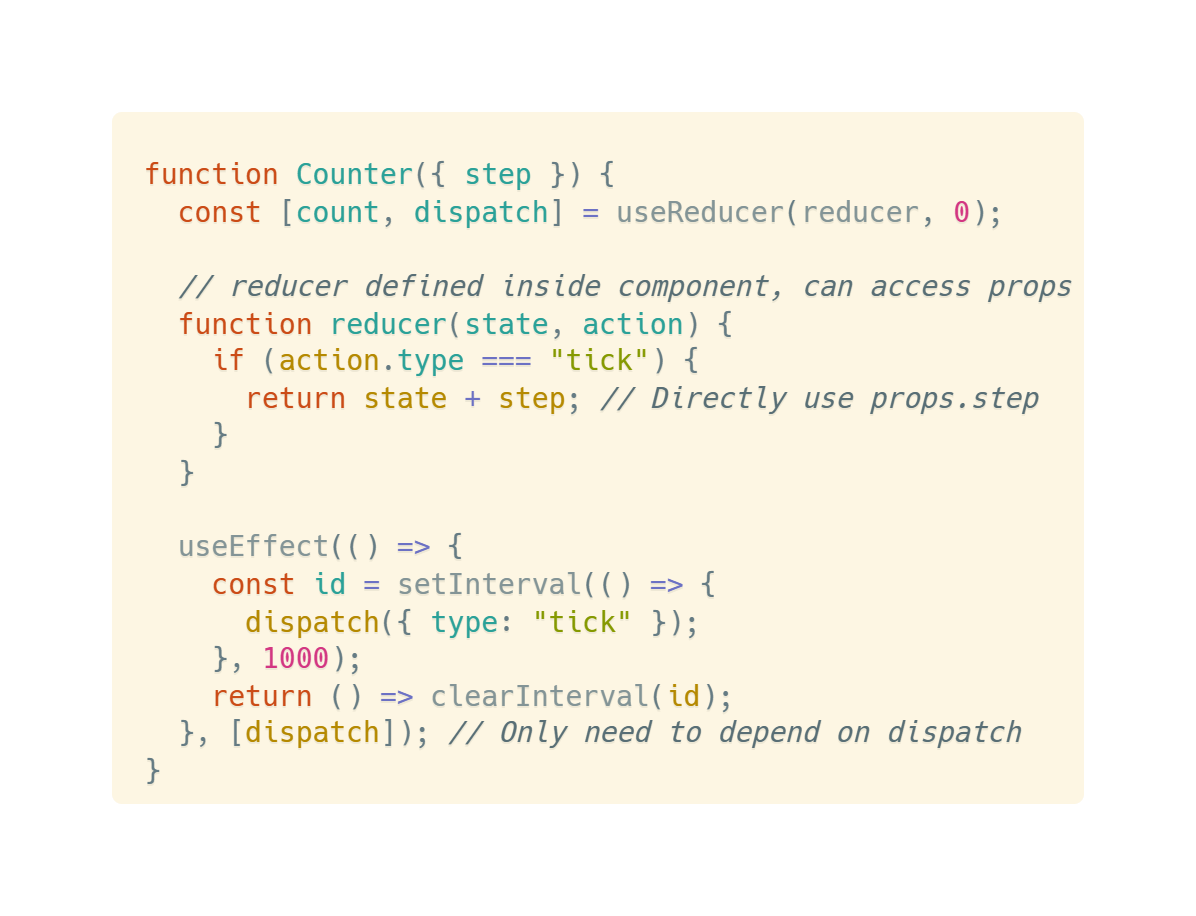

Solution: Use useReducer, specific example:

Complete execution flow comparison:

-

Original version

-

User changes input →

setStep→stepstate updates -

stepchanges →useEffectre-runs → timer resets -

New timer starts, calling

setCount(c => c + step)every second

-

-

Improved version

-

User changes input →

dispatch({ type: 'step', step: new value }) -

Reducer handles action → updates

state.step -

useEffectdoesn't re-run becausedispatchhasn't changed (React guaranteesdispatchfunction is constant throughout component lifecycle) -

Timer continues running, sending

{ type: 'tick' }action every second -

Reducer uses the latest

stepvalue to calculate newcount

-

This way the timer doesn't reset but still uses the latest step value for calculations!

This is the essence of "decoupling": the effect doesn't need to know specific business logic, only needs to tell the system "time's up," while state update logic is centrally handled in the reducer.

This approach brings important architectural improvements:

-

Separation of concerns: Effect no longer needs to read state but dispatches actions describing "what happened"

-

Centralized logic: Reducer centrally handles all state update logic

-

Decoupled design: Effect doesn't care how to update state, only needs to tell the system what happened

The above example solves the problem of "when two state variables depend on each other." Next, let's look at another situation: "needing to calculate next state based on props."

Dan explains this situation and its solution in the "Why useReducer Is the Cheat Mode of Hooks" section.

When our component needs to receive props and use these props in effects to update state, the traditional approach forces us to add props.step to the dependency array. This seems unavoidable but actually causes performance issues with frequent effect re-runs.

Solution: Define reducer inside the component

Define the reducer function inside the component, allowing it to directly access current render's props. Specific example:

Note that while this pattern is powerful, Dan also reminds that this disables certain optimizations, so in practice, only use "internal reducer definition" when you really need to access props in the reducer. In other cases, it's better to define the reducer outside the component.

Finally, Dan calls using useReducer the "cheat mode" because it provides an elegant decoupling way to achieve:

-

Logic separation: Separate update logic (what to do) from event description (what happened)

-

Dependency minimization: Help remove unnecessary dependencies, avoiding excessive effect execution

-

Performance optimization: Reduce re-renders and effect re-runs

[Method 3: Moving Functions Inside Effects]

A common useEffect mistake is developers often think functions don't need to be listed in dependency arrays. This error seems harmless but leads to serious data flow synchronization problems as component complexity grows.

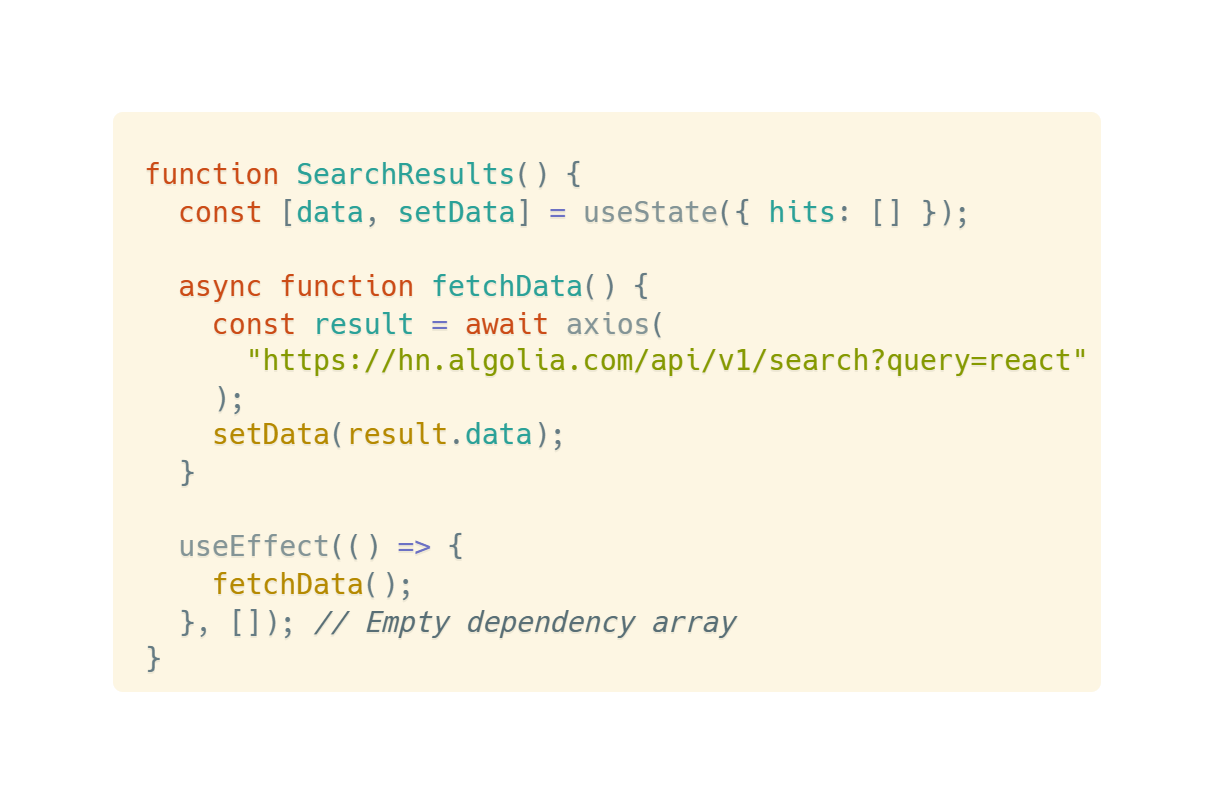

Let's look at the problem evolution process:

-

Stage 1: Seemingly normal code

This code works fine on the surface, but Dan points out the core problem: when component scale increases, it's hard to ensure we've handled all cases.

-

Stage 2: Hidden dangers with increased complexity

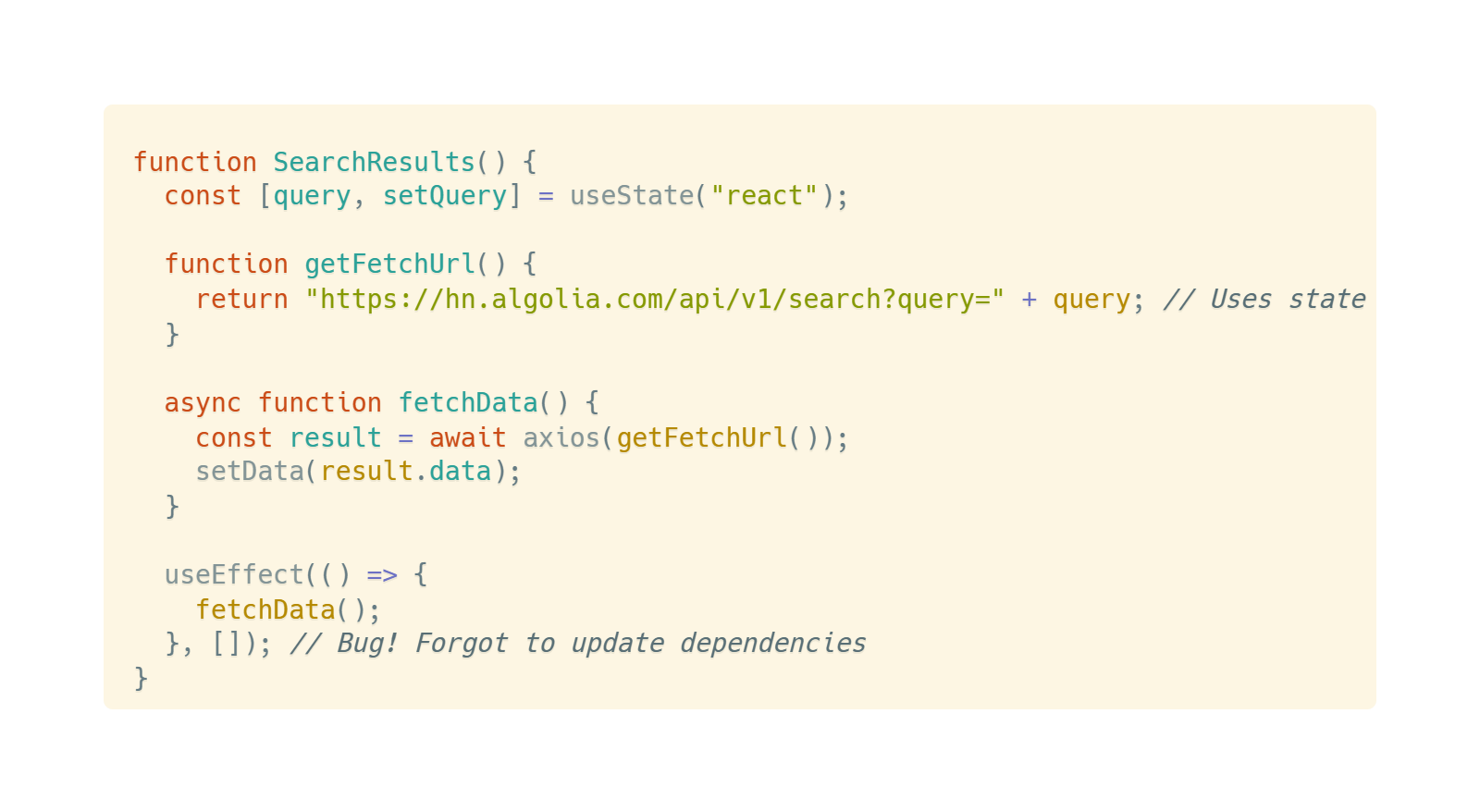

When functions become larger and more complex with interdependent calls:

-

Stage 3: Bug manifestation

When we start using state or props in these functions, problems are exposed:

If we forget to update effect dependencies, the effect won't synchronize with props and state changes, causing data inconsistency.

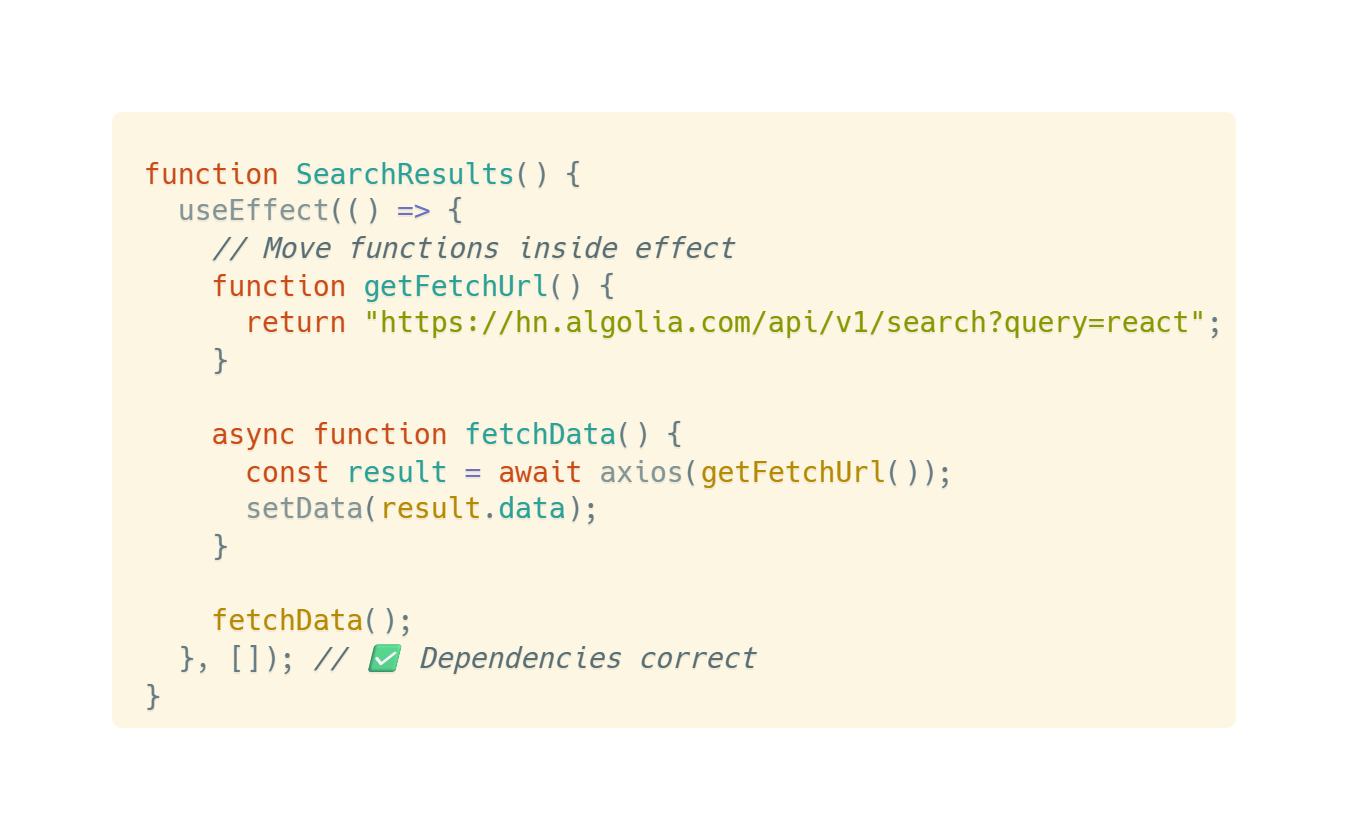

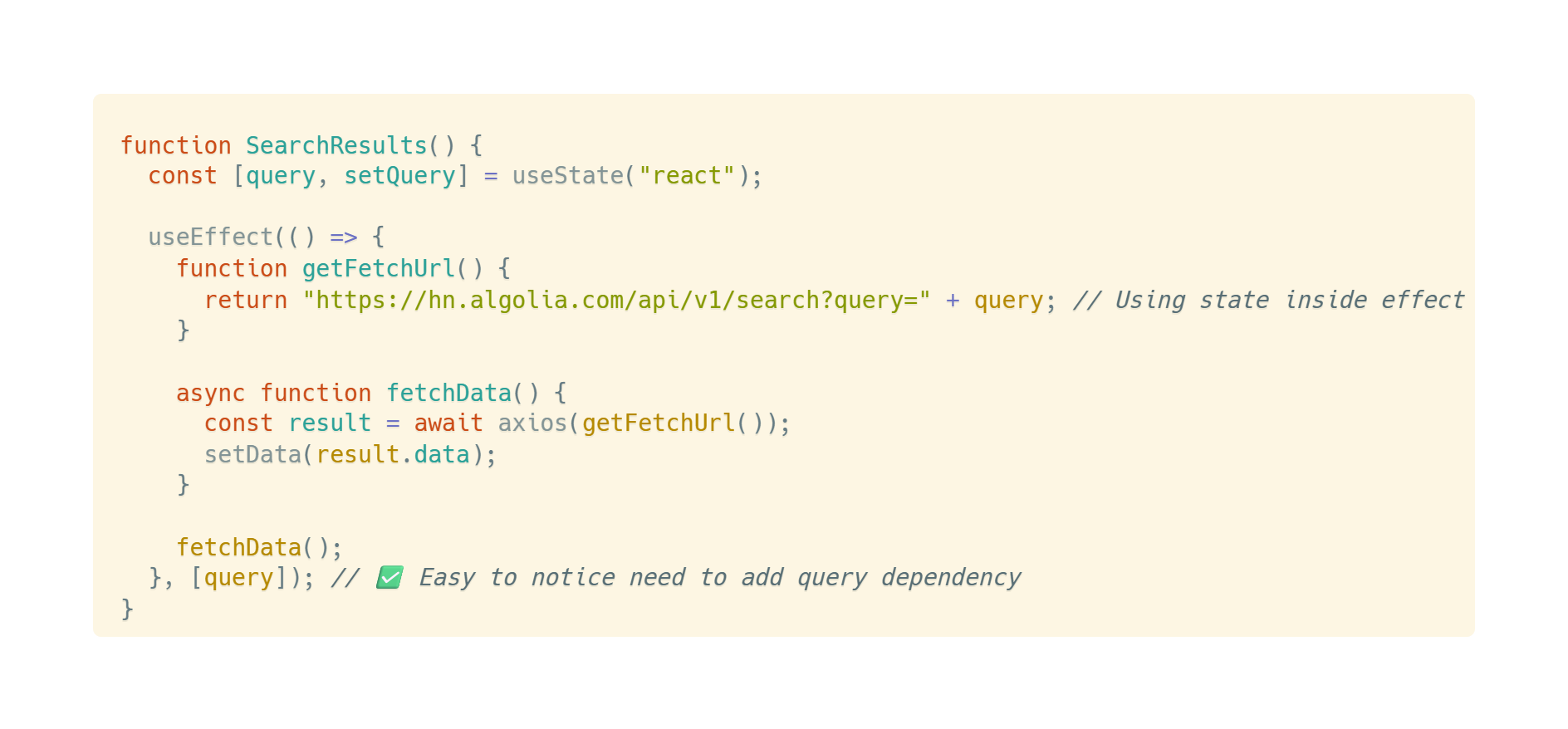

Solution: Move functions inside effects

Dan presents a clean and effective solution in "Moving Functions Inside Effects": if certain functions are only used inside effects, move them directly into the effect.

Advantages of this approach:

-

Eliminate transitive dependencies

Moving functions into effects eliminates the need to think about complex transitive dependency relationships. The dependency array becomes honest: we indeed aren't using anything from the component's outer scope.

-

Natural code reminder mechanism

When we later modify these functions and introduce state:

Because we're directly editing these functions inside the effect, we more easily notice we're using outer variables and need to add them to dependencies.

Dan emphasizes this solution embodies useEffect's design philosophy: useEffect's design forces you to notice data flow changes and choose how your effect should synchronize with these changes rather than ignoring them until users encounter bugs.

Adding query as a dependency isn't just to "please React" but because re-fetching data when the query changes is logically correct.

In summary, we can see that moving functions inside effects - this seemingly simple refactor - actually establishes a clearer mental model, making data flow dependencies obvious and maintainable.

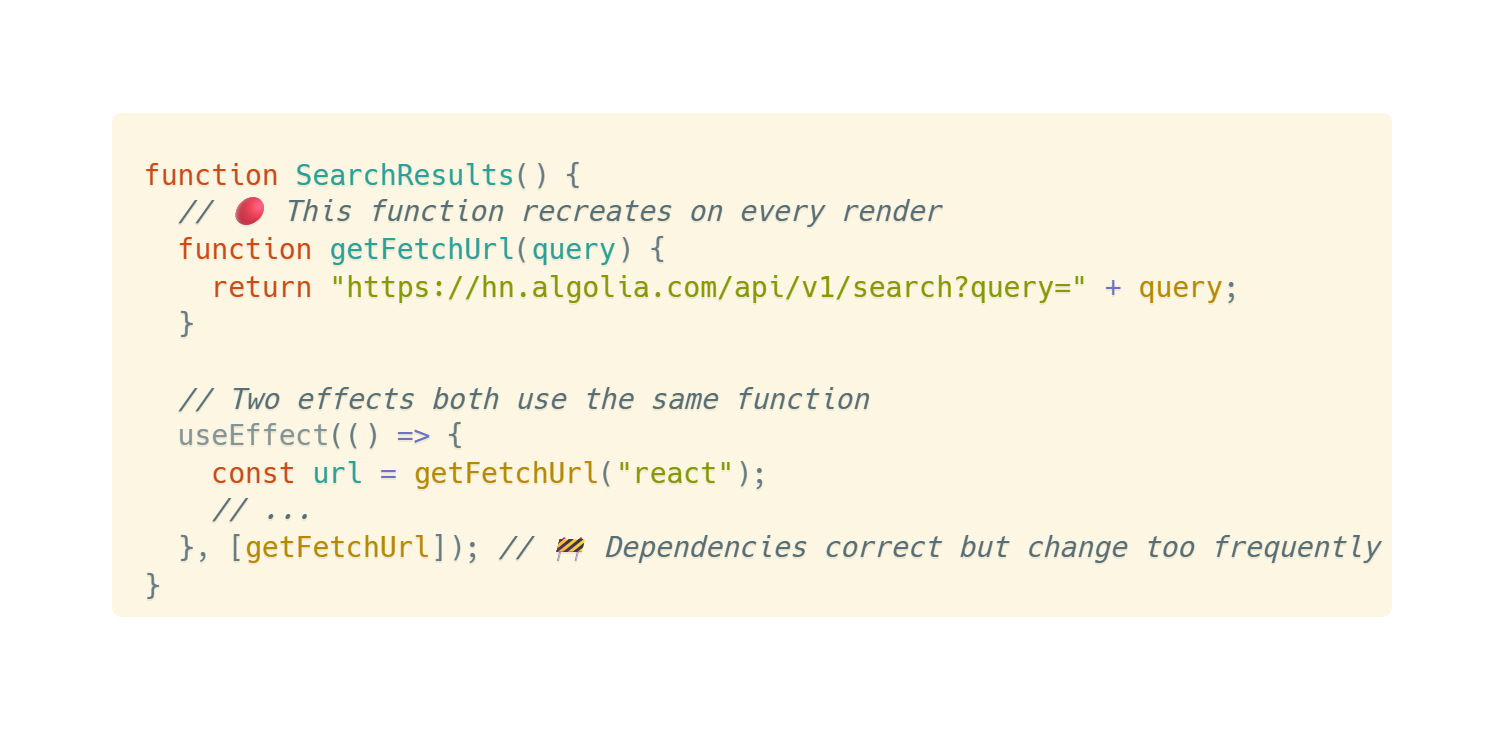

But this method encounters a dilemma:

When you have a function used by multiple effects, you can't move this function into each effect because that would cause code duplication. Here's a specific example:

This causes effects to re-run on every render because getFetchUrl is a new function each time.

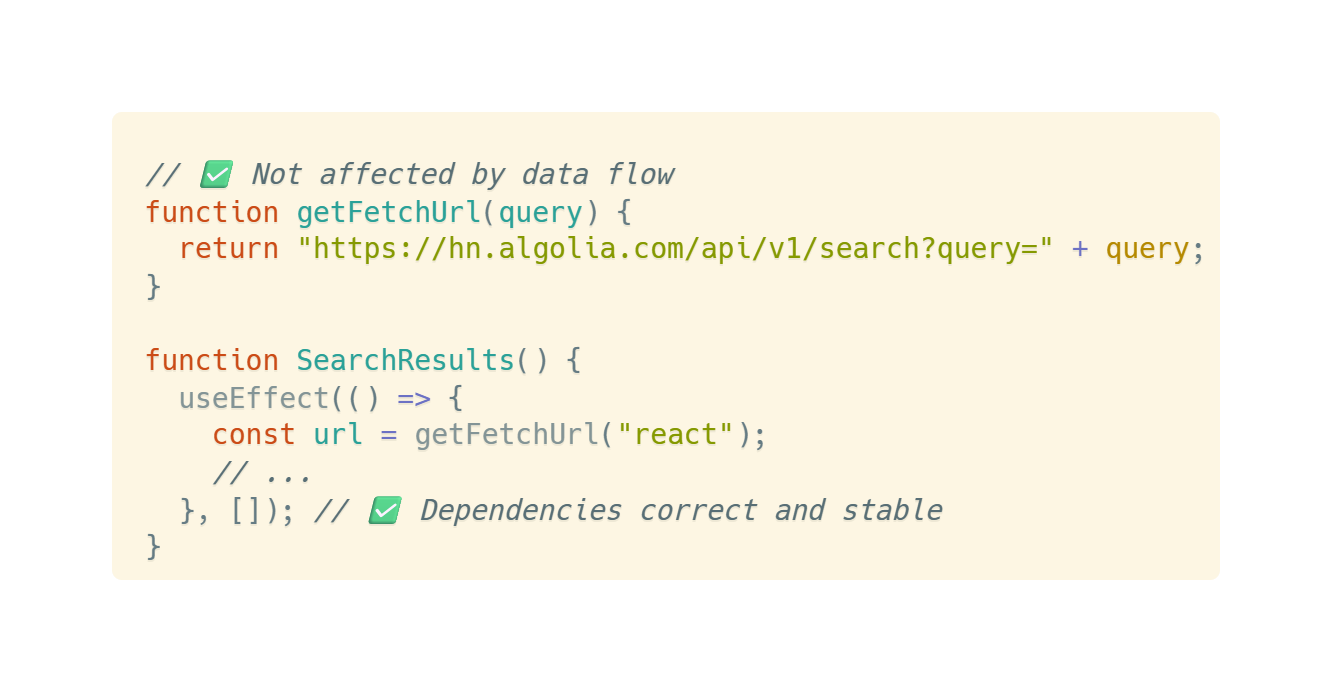

[Method 4: Lifting Functions Outside Component]

Therefore, in "But I Can't Put This Function Inside an Effect," Dan explains one solution when encountering the above situation: lift functions outside the component. If a function doesn't use any data from component scope (props, state, etc.), move it outside the component:

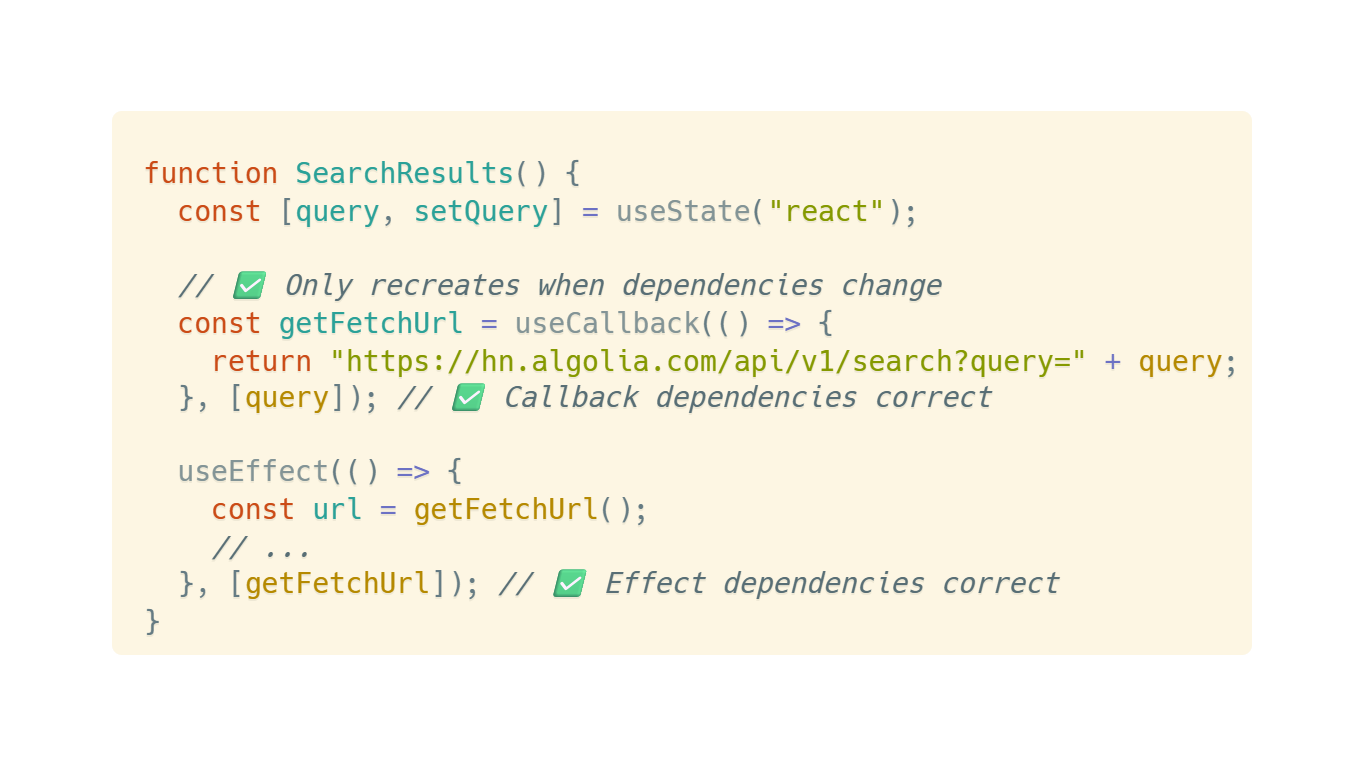

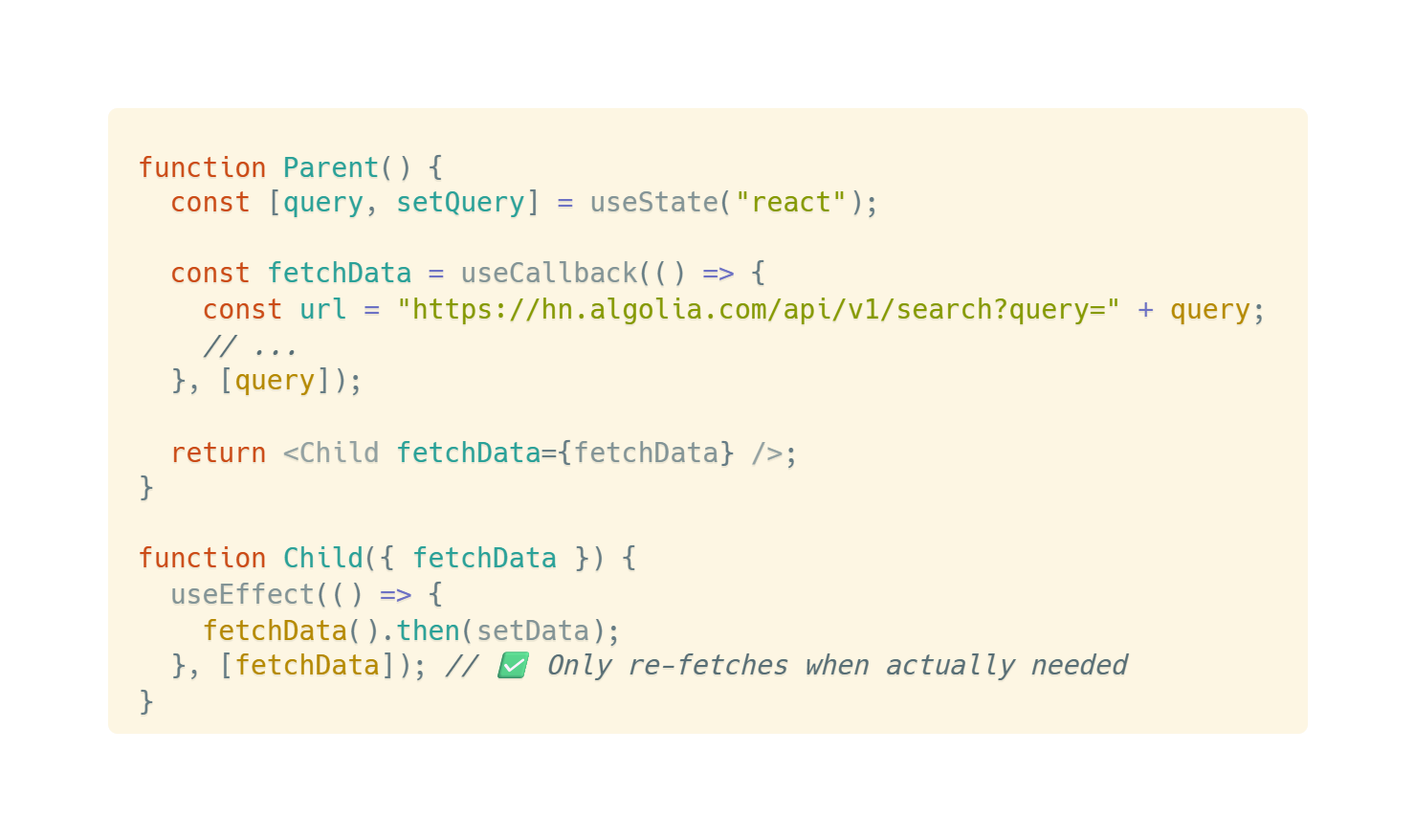

[Method 5: Using useCallback Hook]

Another solution is using the useCallback Hook. When functions need to access component-internal state or props, use useCallback:

useCallback essentially "adds another layer of dependency checking." It doesn't avoid function dependencies but makes the function itself only change when necessary.

Dan uses Excel spreadsheets as an analogy: when you change a cell's value, other cells using that value automatically recalculate. Similarly, when query changes, getFetchUrl also changes, triggering related effects.

This solution also applies to function props passed down from parent components:

Dan emphasizes this solution embodies "embracing data flow and synchronization thinking." Through proper use of useCallback, we can ensure:

-

Effects honestly declare their dependencies

-

Only re-run when truly needed

-

Maintain code maintainability and logic sharing

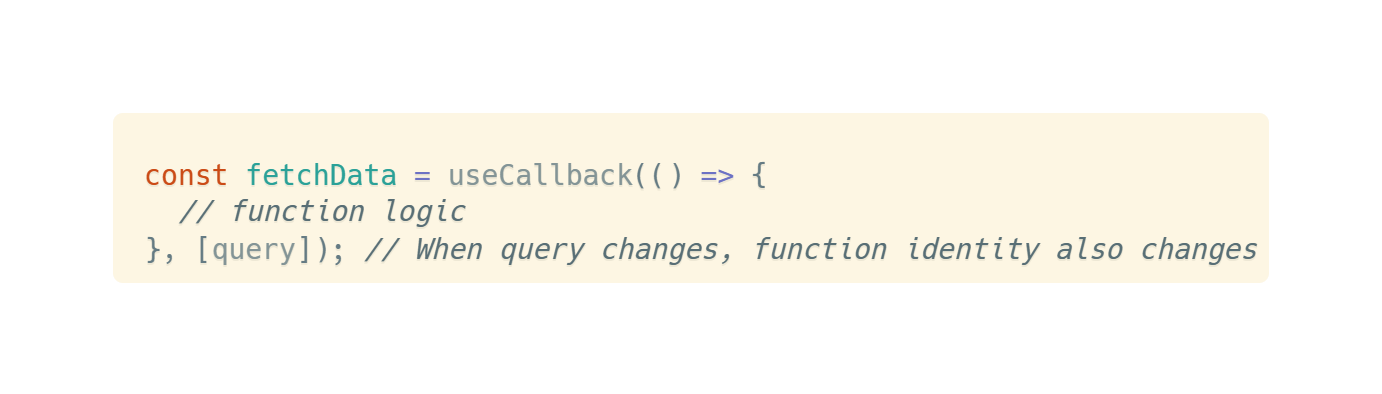

In the later "Are Functions Part of the Data Flow?" section, Dan further explains useCallback.

useCallback allows functions to become part of data flow by linking function identity with its dependencies:

React's another Hook: useMemo uses a similar concept.

Additionally, Dan emphasizes not to overuse useCallback - using it everywhere looks clunky. Here are appropriate use cases:

-

Function is passed to children and called in child's effect

-

To prevent breaking child component memoization

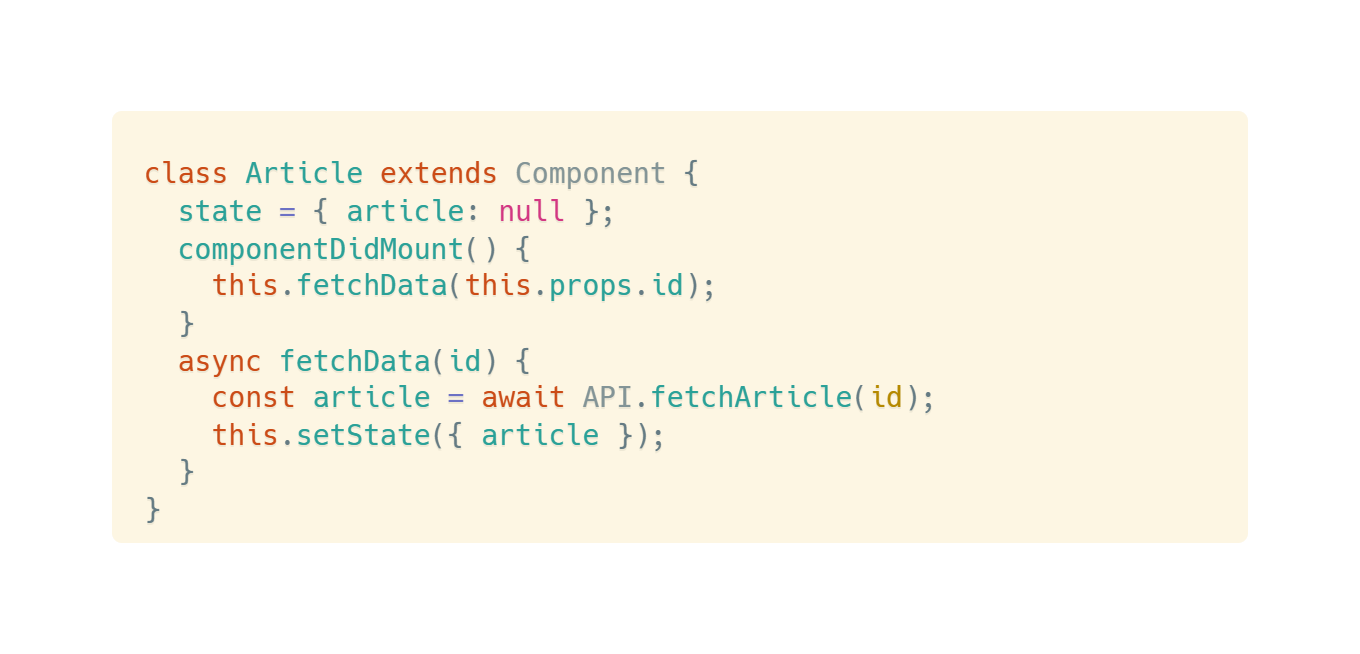

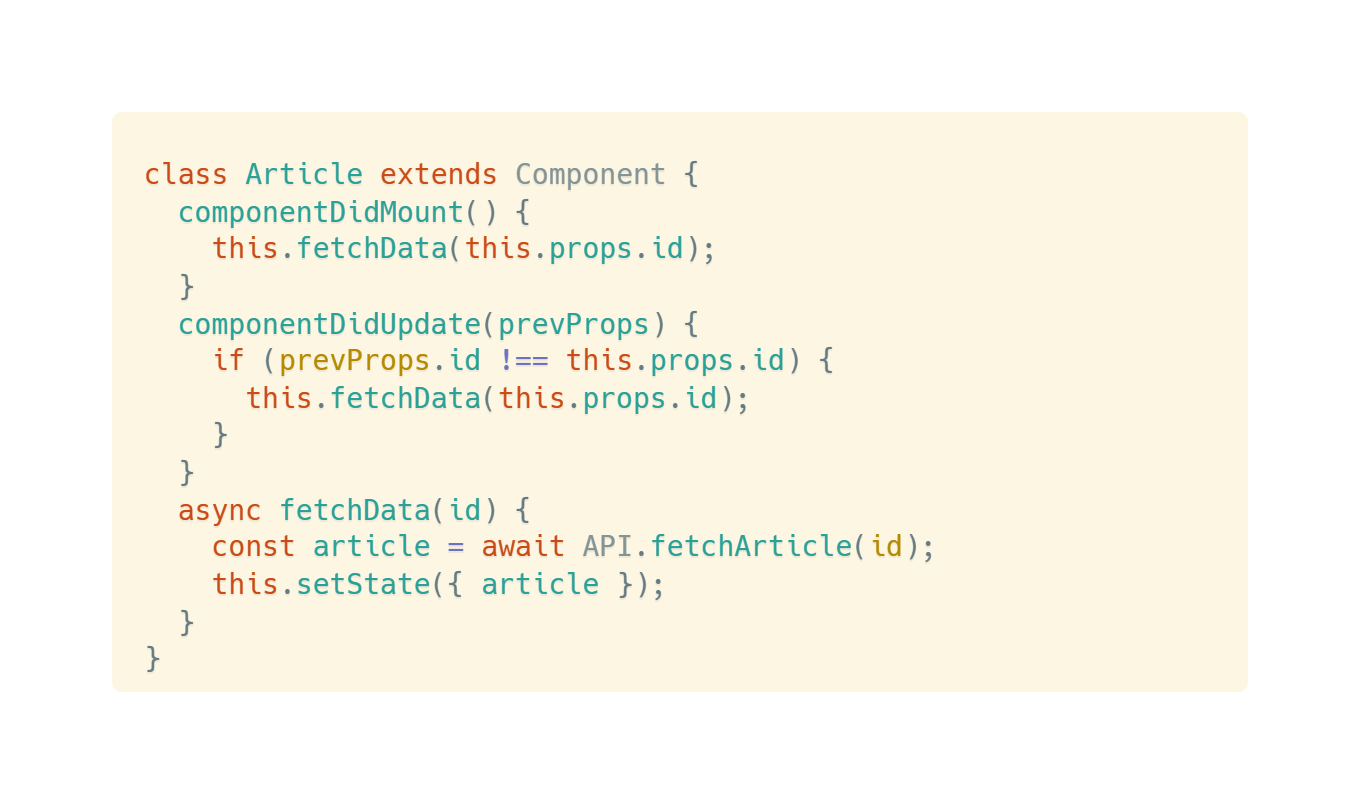

Strategy 3: Handling Race Conditions

In "Speaking of Race Conditions," Dan clearly explains the classic problems encountered when handling asynchronous data fetching through three stages of code examples, and how useEffect handles these problems.

Stage 1: Basic but flawed implementation

This version only fetches data when component mounts, completely unable to handle props updates. If id changes, component won't re-fetch data, causing stale content display.

Stage 2: Handling updates but still problematic

This version seems to solve the update problem but introduces more serious race condition issues.

What is a race condition?

Let me step out to explain race conditions - they occur when the execution result of two or more operations depends on their execution order, but this order cannot be guaranteed.

This is a problem all programming languages supporting concurrency or multi-threading face, and the unpredictable order is mainly because operations on shared resources in concurrent environments aren't atomic.

So we can summarize that race condition problems have three key factors: concurrent execution, shared resources, and non-atomic operations, while JavaScript's asynchronous operations are a common way that leads to concurrency.

Here's more detailed explanation of the three key factors causing race condition problems:

-

Concurrent execution:

-

Multiple instruction flows running simultaneously

-

This could be multi-threading, multi-processing, or asynchronous operations in single threads

-

-

Shared resources:

-

Multiple execution flows accessing the same resource (memory, files, etc.)

-

No shared resources means no competition

-

-

Non-atomic operations:

-

Single logical operations actually consist of multiple steps (like read-modify-write)

-

These steps might be interrupted by other execution flows

-

Real race condition scenario example

Suppose user quickly switches articles:

-

User clicks article ID 10 → sends request A

-

User immediately clicks article ID 20 → sends request B

-

Due to network conditions, request B returns first → correctly displays article 20

-

Request A returns later → incorrectly overwrites state, displays article 10

This is race condition: even though user finally chose article 20, because request A completed later, it incorrectly displays article 10.

[Solution 1: Support Cancellation]

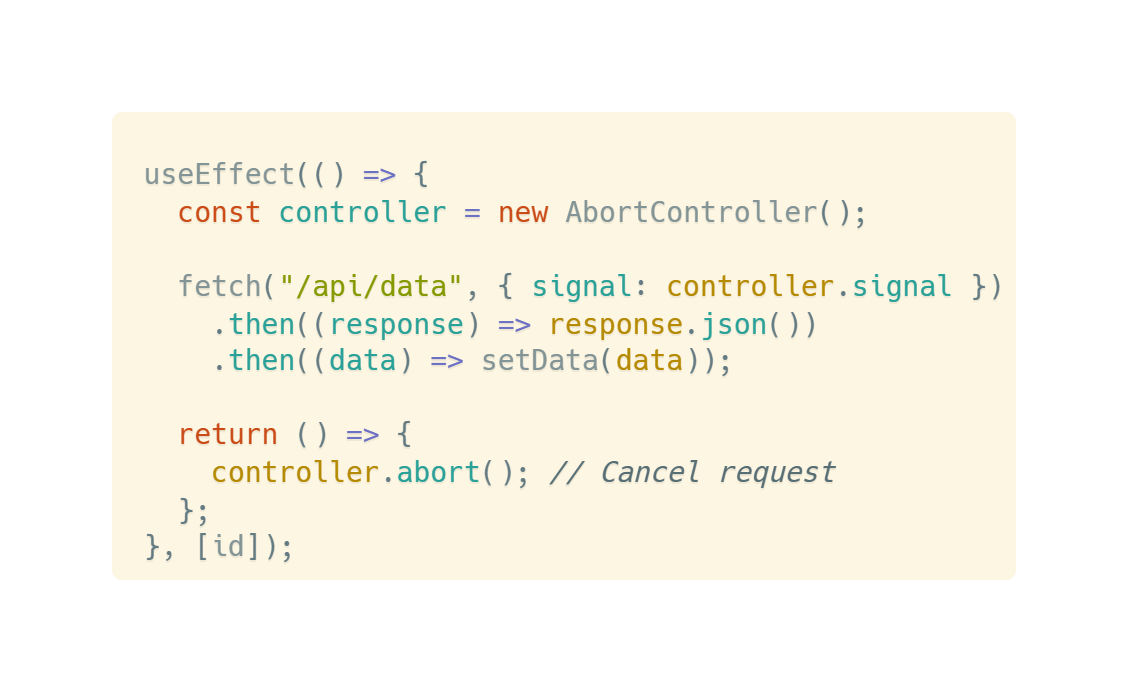

If your asynchronous method supports cancellation, great! You can cancel asynchronous requests in cleanup function:

[Solution 2: Boolean Flag Pattern]

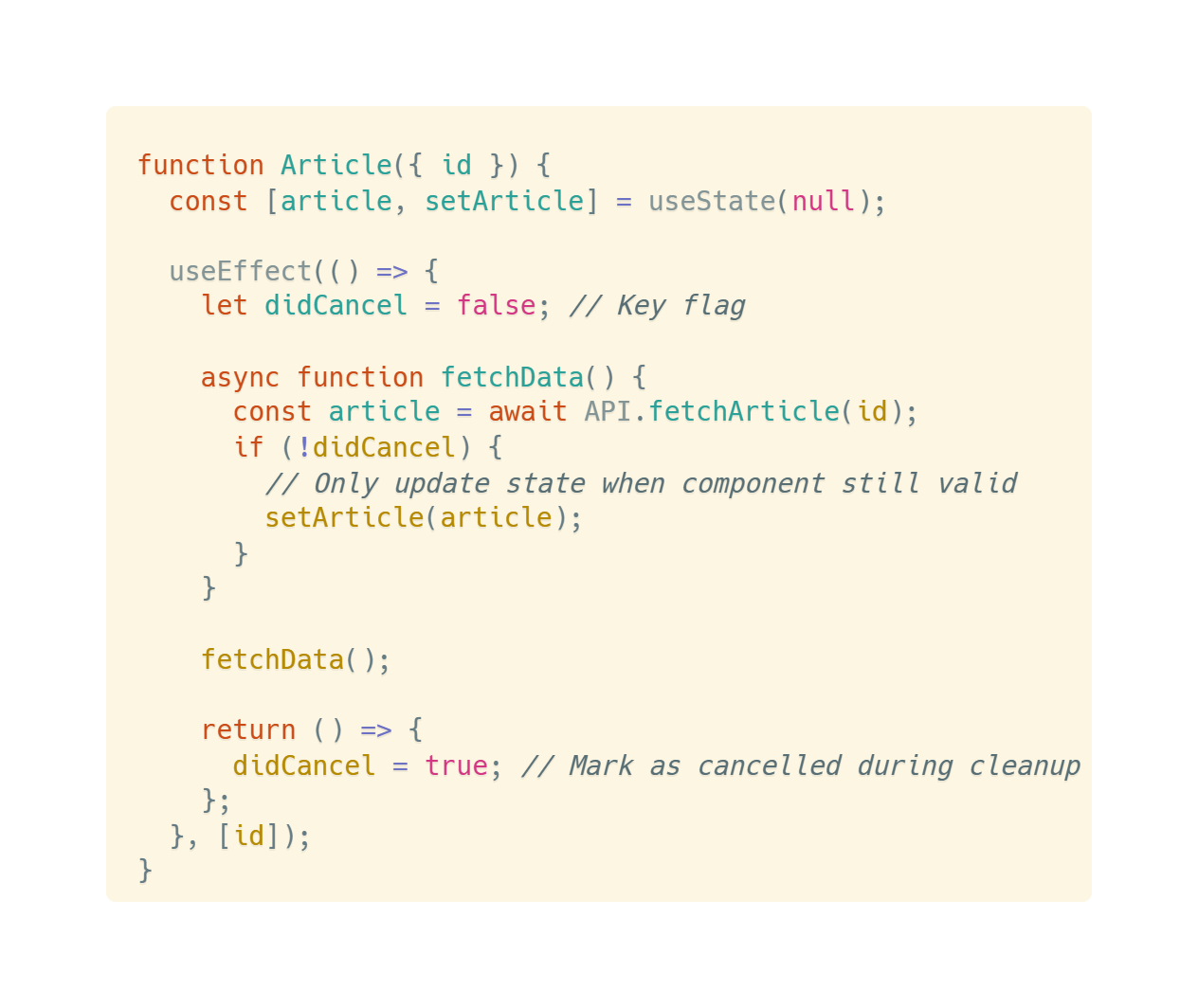

This is the simplest temporary solution, using a boolean variable to track whether component is still valid:

Conclusion

Finally, it's important to emphasize that useEffect's real value lies in synchronization thinking - it makes side effects part of React's data flow, ensuring component behavior consistency. While it has a higher learning curve, once mastered, it significantly improves applications' ability to handle complex situations.

In summary, useEffect isn't just a tool to replace lifecycle methods but a completely new way of thinking about React component synchronization.